I'd have been listening to Dizzee Rascal and Florence & The Machine as a student. Time flies.

I was talking to a student interested in startups and shared some stories about how I’d ended up joining Yonder.

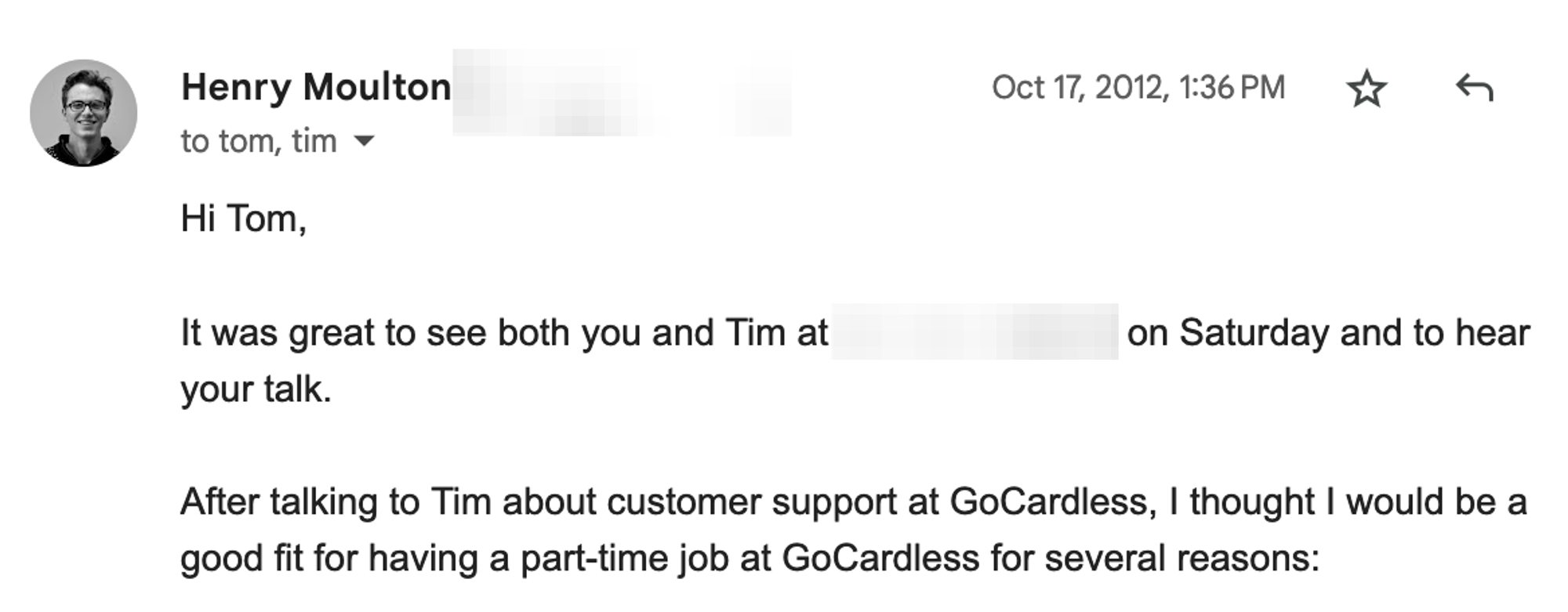

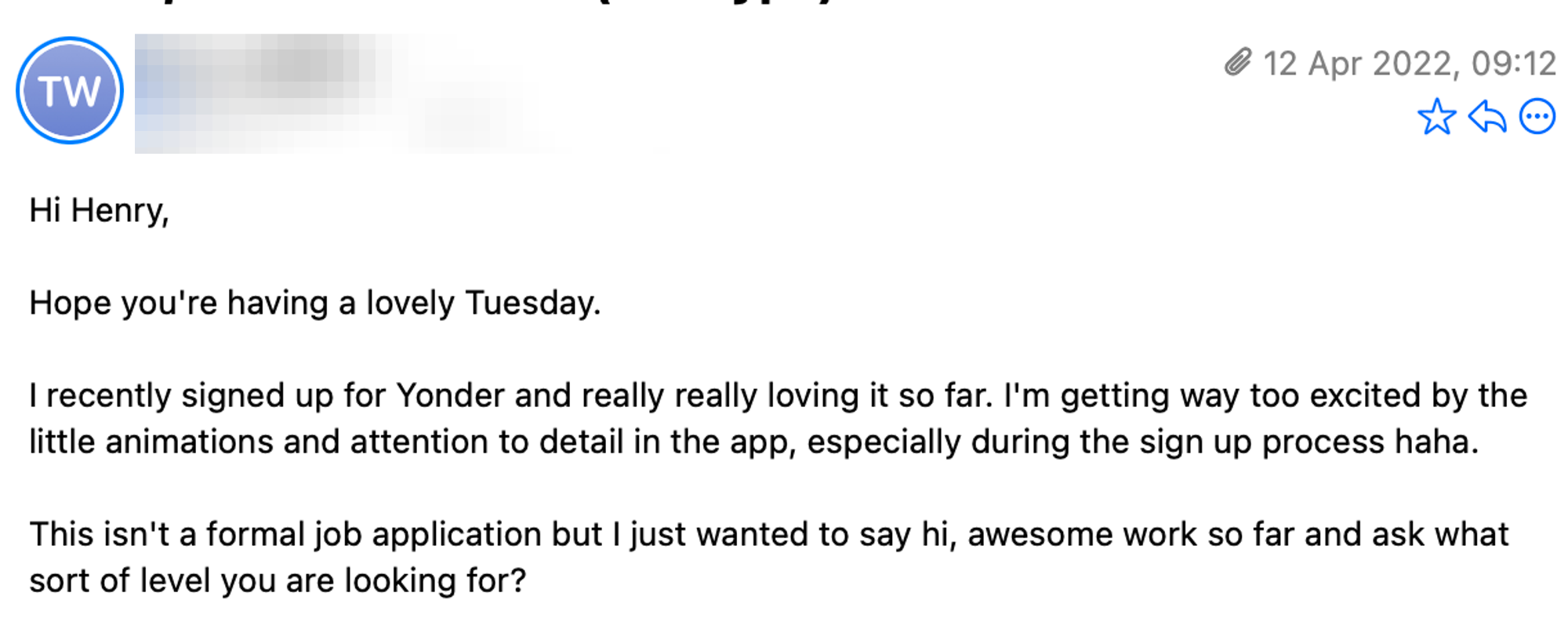

The enthusiasm and energy of the student reminded me of the time I was 19 and a student looking for a job. London didn’t have many good startups in 2012 but there was these smart guys that I’d met who had come back to London from Silicon Valley to build a fintech startup. So I thought I’d email:

GoCardless wasn’t interested in a 19 year old working part-time.

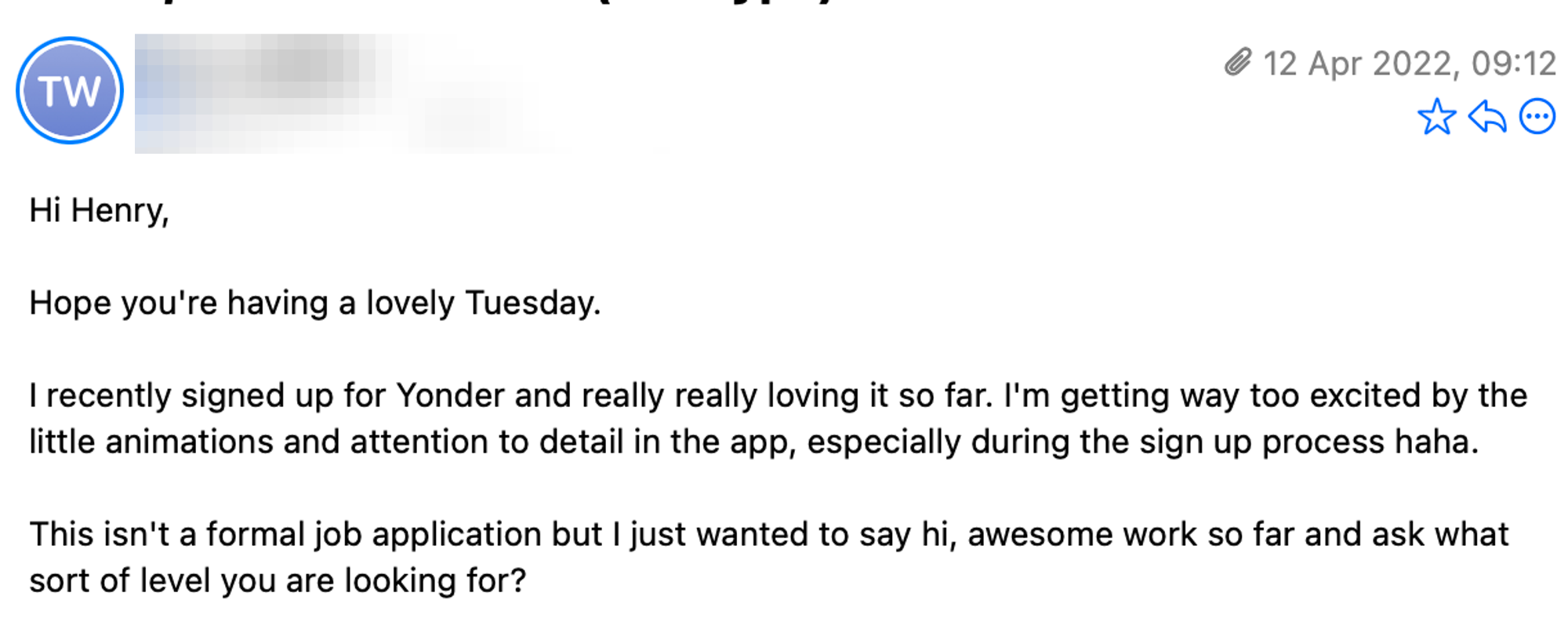

But 10 years later, I received a similar looking email myself:

Getting more students interested in startups probably can't be a bad thing, so now feels like a good time to share how I started building Yonder’s app.

—

Who starts a credit card?

“The idea sounds alright… but there’s these guys starting a credit card. You should chat.”

About 2 and a half years ago I was doing some software contracting work at Amazon. Playing around with a startup idea on the side, I asked Gideon for a chat. Gideon was part of my batch on Entrepreneur First and we had this call where I laid out my vision for all-in-one visas, taxes, investing and accommodation for remote workers. Then he told me “The idea sounds alright… but there’s these guys starting a credit card. You should chat.”

And I remember ending the call thinking…

“Who starts a credit card? How do you even start a credit card?”

But next to those questions lived an idea that was stuck in my head. It was pervasive. It hadn’t left me since I was a teenager.

“I want to build an app from scratch, with a great team, and it has got to be a product people love and use in their everyday lives.”

Or more simply,

“I want to make software people love, and I don’t want to do it alone.”

When I was younger apps were being launched all the time. But now opportunities to build apps people use in their everyday lives is rare.

There's only a few categories that are worth it: Communication, Entertainment, Travel/Navigation and Finance and within that you’re competing with some of the strongest companies or most regulated industries. Google, Meta, Netflix, Big Banks, Neo Banks.

To get new customers, you’ve got to convince them to - wait for it - download a new app on their phone. What a nearly insurmountable barrier to entry that is. Consumer behaviour is illogical, confusing, and downright irrational. Only first-time founders or the crazy build consumer software.

Consumer software is rarely built in London. Look at your phone, the device you spend every waking hour using and has completely remapped how society works. How many of the apps were made in London? The only thing London excels at is consumer fintech. I’d pinpoint sometime around 2015, maybe when a16z came from Silicon Valley to scoop the Wise Series B, as around the time we could say London was starting to compete.

I’d been building apps as a freelancer for many years. I knew how tough it was. How much easier it would be to join a B2B SaaS HR startup and call it a day. But there's a difference between building a great business and building great software. I'm still unsure who loves making HR software. Or a lot of enterprise software for that matter. It's possible, but software is the closest thing we have to magic, it shouldn’t feel boring!

Why was I so obsessed with making an app anyway? It was something I hadn’t grown out of. It wasn’t cool anymore. The golden age of social, local and mobile apps was over. Apps weren’t a new thing. It was 2021, mobile had already eaten the world. I wasn’t into something more trendy like AI or web3. I’d gone through a startup accelerator trying to find something else to get excited about. That hadn’t worked as I spent about half of it trying to understand if Pinduoduo’s success in China was replicable in the west.

But despite the lack of trendiness, smartphones and apps were what I grew up with. They’re the defining computer platform that gave the whole world access to software and the internet.

And there’s just something about building apps that I hadn’t found anywhere else. It’s cross-disciplinary in a unique way. The combination of smartphone only APIs, innovation in UI design, offline data stores, gesture handling and animation wasn’t part of building websites or backend services. Building apps means becoming familiar with spring physics, trigonometry, geospatial point clustering, typography, colour theory, touch handling and so many other parts of knowledge all while having to run at 60 frames per second even on the lowest power devices.

The challenge of apps is balancing the engineering pursuits of correctness, reliability, security, performance with the design pursuits of usability, aesthetics, accessibility and easy of use. All to make something people want to download.

I just wanted to give it a proper shot. From scratch. Something I'd use everyday, maybe someone else would use everyday.

And a credit card is something you might use nearly everyday… how do you even start a credit card anyway? It that legal?

Negotiating

So I hop on a video-call with Tim, the CEO.

From what looked to be a cupboard, Tim told me:

“We're going to build a new credit card in 6 months. We don't have any designs, brand or app. Actually, we don't even have a name. Oh and the app has to be better than Monzo and Revolut. Are you interested in joining?”

I thought about it for a few days. I looked down at my phone, scrolling through the apps. I looked at my AMEX app. The offers page. The transaction in the list when I got my cashback. It wasn’t bad but I remember thinking to myself, “I think this can be better”.

The interview process was walking Harry (CTO) through a prototype codebase he’d written and what I’d do differently. I chatted with Theso (CRO) and Craig (Design) on how engineers can work with designers. We went onto talk about the nature of aesthetics, taste and the problems design systems pose to creativity. (I think other people were thinking about the same stuff around then).

I spent a bit of time umming and erring. I did due diligence by asking around into companies that might launch a credit card in the UK. I figured Monzo, Chase and maybe even Apple would launch in the UK. I read annual reports of American Express, Visa and Mastercard and realised that these companies have a monopolistic chokehold on the industry. While I could see you could maybe make a better product, I couldn’t see anyway a new credit card had a chance to become a great business.

Luckily, Tim offered for me to speak to Remus, a General Partner at one of Yonder’s early investors LocalGlobe. Back in 2016 I’d actually already dropped everything and interned for a LocalGlobe portfolio company, Lingumi. (In retrospect, if it’s got LocalGlobe money in it, the team is going to have some great people.) He’s a busy guy but I’d managed to get about 20 minutes of his time in the morning. So he’s there on a video call eating his bowl of cereal (was it Cornflakes or Weatabix?), and he said something during the conversation that really stuck out to me:

We looked into the team and found the most quality set of co-founders to go start this thing.

Something about the way he said “quality” stuck out to me. Slowly and almost italicised. Quality.

After that we chatted about all the ways the business could fail. We chatted about the rise and fall of Wonga and why most investors won’t touch consumer borrowing companies in the UK.

But I’d become unfazed. A sense of clarity. He’d said something, but really showed a feeling, an emotion, about the founders. This is a guy who spends thousands of hours every year poring over pitch decks, and cross-analysing founders to see if they have the tenacity to succeed.

Build an app from scratch. Remus said it was a quality team. What was I missing? I was thinking of moving out of London. I’d been there all my life, stayed through the pandemic. I figured a move would be good for me.

The negotiation went something like:

“We can’t pay you much, and we’ll have equity, board seats and you won’t. But we’ll give you some stock options which you can treat as lottery tickets.”

“Awful, but I get to build an app from scratch?”

“Yes.”

“It’s a terrible deal, but I’ve been in London my whole life, how about you let me work fully remotely after a year? Deal?”

“Deal.”

So I quit my first ever BigTech contract early to go join 3 co-founders and a designer who were working out of a structurally unsound building on Pentonville Road.

How I made that decision:

Worst case: Yonder would be out of business in less than a year, I’d have made an app from scratch and would go back to contracting or have a go at that startup I’d told Gideon about.

Best case: I get to leave London (a story for another time), and make a 5 star app myself and others enjoy using.

I didn’t think about the lottery. Startups are too fragile. Death should be expected. A startup can look like a sure win, and still die. Don’t join an early stage startup for the money. Either do it to build, learn or to escape the emptiness of a big corporate job where your contributions are utterly meaningless. Ideally all three.

So the founders, Craig, and the new hires, Tom, Torpy and me had a barbecue at Theso’s. I wasn’t drinking much at the time. Just before arriving I panicked about turning up empty handed so headed to an off-license and bought half a bottle of vodka and a lime. The first impression I gave everyone was that either I was an alcoholic or thought it was Fresher’s Week. Off we go.

Starting a bank is easy. Starting a credit card is hard.

Note: I really hope either Tim, Theso or Prisc will one day tell this story better than me, but it’s worth sharing because I’d often mention it in conversations and people almost wouldn’t believe me.

Starting a bank is easy. People give you money. I didn’t full realise it at the time but a credit card is harder. You give people money, and hope they pay you back. So before you even build an app, you have two big problems.

The first problem is you have no money. And you need money to let people borrow money from you. How do you solve that?

Well Tim had to go put on a blazer and go to Mayfair (on a Lime bike) and make a deal with some of the toughest people in finance - debt funds.

When he came back victorious I imagine this was the conversation:

“Hi I’d like to borrow £15 million pounds please”

“Why?”

“There’s me and 6 others working on a new credit card, we’re going to go compete against American Express, Chase, Apple, Barclaycard, and the neobanks like Monzo, Starling, Wise and Revolut. We don’t have a product just yet.. or a full idea of what the product will be, and we haven’t underwritten any customers because we don’t have any, but trust me on this one. We’ll pay you back. We’re a serious business. We build our own desks, some of the lights don’t work and the house plants are withering. We don’t have a cleaner so one of us is the VP of Bins and one of us is VP of Dishwasher. We can only afford standing desks if they're made of cardboard.”

“Sounds legit, where do I sign?”

So you get some money. Perfect. Now you’ve got a bigger problem. You’re letting anyone fill out a form in your app and giving them the right to borrow thousands of pounds from you, and you’re left hoping they don’t take the money and run.

You’re walking this tightrope of trying to make the product experience of signing up the most easy, seamless experience… while making sure you’re signing up people who will pay you back. You’ve got to find, to use the lingo, “intent to pay customers”.

You’re diving into the world of credit bureaus, regulations like the Consumer Credit Act, rules like Consumer Duty, and entire sub-industries with acronyms like AML, PEP and KYC. You’re building underwriting models. You’ve got to find a manufacturer for the card. And then magically your card has to work with every ATM and payment terminal on the planet otherwise your card is going in the bin.

I didn’t do any of this stuff. I just sort of watched in the office every week as it came together from a group of talented relentless individuals who weren’t going to get pushed around. You hear in startups that it’s all about hiring and talent. The early days of Yonder was the transformation between that being advice I’d heard and having the lived experience to really know it.

All this to make a product you hope people want to tell their mates about. Except credit cards are a bit taboo in the UK so forget about that happening. Also to add some extra difficulty the card is about £200 a year and doesn’t really make sense outside of London.

All of this was being setup while I got to work on an app...

2021

2021 was a lot of building. I joined in June. I remember feeling confident that I’d joined the right environment when Harry gave me the initial Onboarding APIs. “Alright we have a flow chart, just get going on building an app”.

Yonder was intense and high pressure but having made apps for fun since university, the first few weeks reminded me that making, creating, and building is enjoyable.

But that summer the app looked bare bones because we hadn’t decided on a brand, so we hadn’t decided on a visual design. That meant I was building something that I was sheepish to show anyone. It looked stark, minimal, boring.

Even so, I was coding so much that in the morning when my alarm would go off my head was full of code I had written the previous day, but my brain hadn’t yet finished processing.

Sometimes on the way home from the office to King’s Cross station I’d come up with an idea, so would sit on the Victoria line platform and just code it out. Then I’d go home and continue coding until 2 or 3am.

I created an doc where I listed all the different technologies and approaches to building apps that we could maybe take advantage of. I invested into code generation, tooling and testing and “app platform” while trying to actually build the product. I not only wrote tests, but invested into a slightly unconventional way of writing tests to fit the startup pace. I bet early on new technologies that would deliver high performance while letting us write in one codebase. Sometimes this would blow up in my face with ridiculously tricky bugs, but every now and again I'd do a build of the app and something would slot into place. One day at a time.

I was trying to fit the iOS and Android apps - requirements, product design, APIs, platform, releases, in my head.

Early on I got feedback from everyone that my ideas across the company were helpful so I was also trying to juggle reading and thinking about every decision being made across the company while making an app.

I was trying to make sure we were building something people wanted. In September I wrote down in our Product Ideas backlog an idea I was a bit skeptical about, but thought maybe worth just writing down “This idea is part of figuring out what would be 'holy shit I need to have this card' value that we can do while finding Product Market Fit.”

We didn't have any brand yet so I tried sending links I'd come across of consumer product vibes I loved in Slack. Poolside.fm, Nude, Vacation. At some point Tom our head of marketing bought me a scented candle from Vacation. When does a man buy another man a scented candle? Awkwardly grateful, I stumbled on my words while trying to say thank you.

Initially the idea was to have another mobile engineer join the team, but we couldn’t find anyone who'd take the pay cut or join a team with no product. We had a great application, amazing technical skill, but who completely bombed the interview with the founders. Not only was I in disbelief, I was almost heartbroken. Hiring was taking up such a large amount of time and I was convinced this would be the perfect fit. That Sunday I delivered a long monologue on how impossible hiring is in startups to my brother’s girlfriend, she could only look at me bewildered.

Every week on Friday there was a product demo, and we had callouts. Someone always had something to announce. Harry built our entire core banking and billing by himself. Harry 2, or Torpy as we called him by now (don’t ask), had learnt Scala and built Direct Debit integration by himself. Tom talked us through our market positioning and reworked our brand. Craig demoed all of our design from logos to app to website to card packaging. Theso talked us through our initial lending model. Tim talked us through fundraising, hiring, strategy.

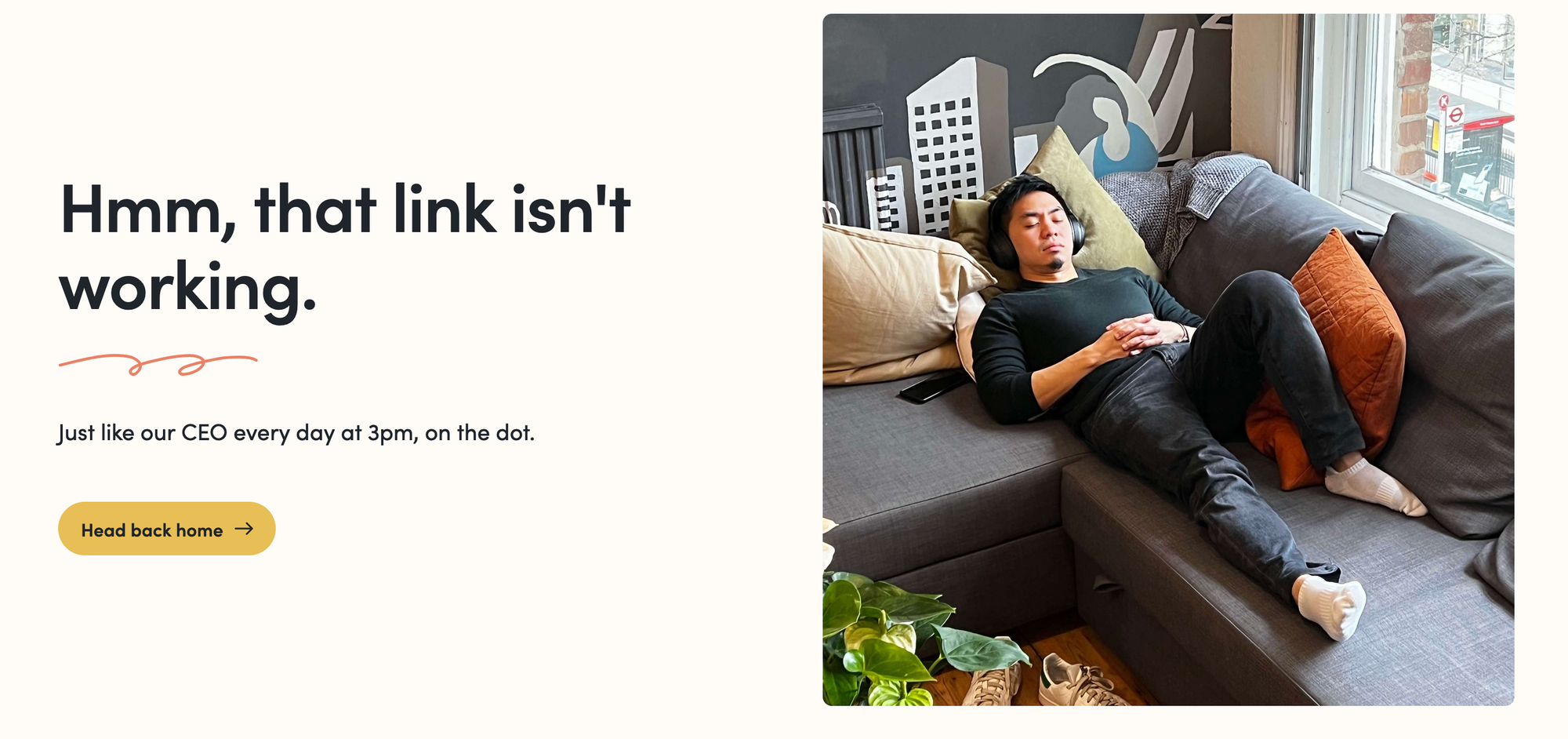

Naps were allowed at Yonder because Tim would either nap or meditate in the office, so obviously this is our 404:

We’d go to deli-licious for lunch and get chicken escalope wraps the size of a newborn baby.

New employees at Yonder are still sent on an exhibition to deli-licious as part of their cultural onboarding into the cult company.

At some point, possibly related to the size of the coma-inducing portions of deli-licious, someone went to Argos and built a hammock in the office.

Autumn was hectic and exhausting. At some point in our insane rush I found myself saying to Torpy our backend engineer “so we’re going to build Experiences next week, that’s fine right?”

The crunch was hard. We all knew the initial app wouldn’t cut it. Craig had gone and created the “proper” designs after a last minute turning around on the brand with Tom. It was last minute and things looked pretty great, but no one was dead certain it'd even be liked. There were some tricky bits. I settled into one of the hardest coding re-writes to get things feeling quality, Yonder-y.

Yonder was built while coming out of the pandemic. That year many in the office suffered personal loss. Stretched at work, stretched at home. We had a group coaching session and within a few minutes someone had to walk out and shed a few tears. I had 1 to 1’s with Harry every week walking around King’s Cross for an hour. I’d brain dump everything across app, product, company, personal life. I'd never really had a manager before, but on those walks along the canal, past Coal Drops Yard and Platform 9 and 3/4, I learnt what a great manager is.

I think at a lot of startups at the end of the week they head to the pub. By late Autumn, Friday was home time. The final meeting would end with an exhausted "what a week". You wanted your bed instead of a pint. In my first coaching session with Yonder’s coach I opened with “I think I’m ok but I just feel really tired, all the time”. (Note: Someone at a Yonder event in 2023 saw a photo of me in 2021 and said "Hen you look ill". In retrospect more sunlight would have been healthier.)

But things were happening. We had an idea of what we were building. We had a card that worked and made transactions. We got regulated. We got more funding. We had hired some more amazing people. We had an app. We picked a name out of a shortlist of names. As I remember it, there were some terrible ones, and no one was particularly excited about any of them. We went with Yonder.

2022

Somehow I convinced Vytautas, a previous colleague to come join as a freelancer and then work full-time with me. He initially said no, all for good, sane, reasons, but over a video call, halfway across the world, I implored “seriously, just trust me on this one”. In retrospect, I don’t advise this as a hiring strategy, but somehow, miraculously (Vytautas balances being an excellent coder and an excellent human), this worked. The weight of every line of app code having to be written by me was lifted. The joy of pair programming and having someone to bounce "hey here's a dumb idea, what if we..." ideas off came back.

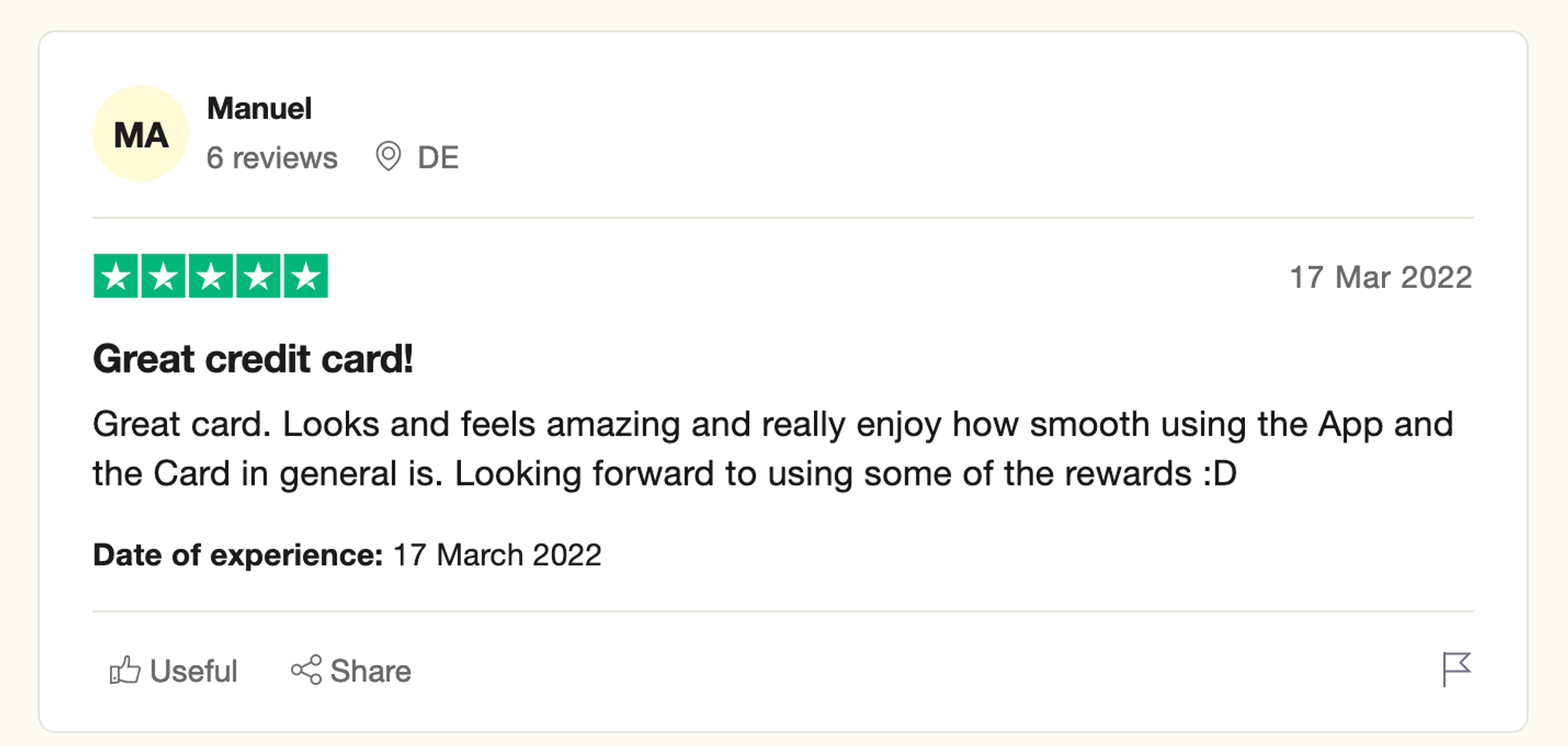

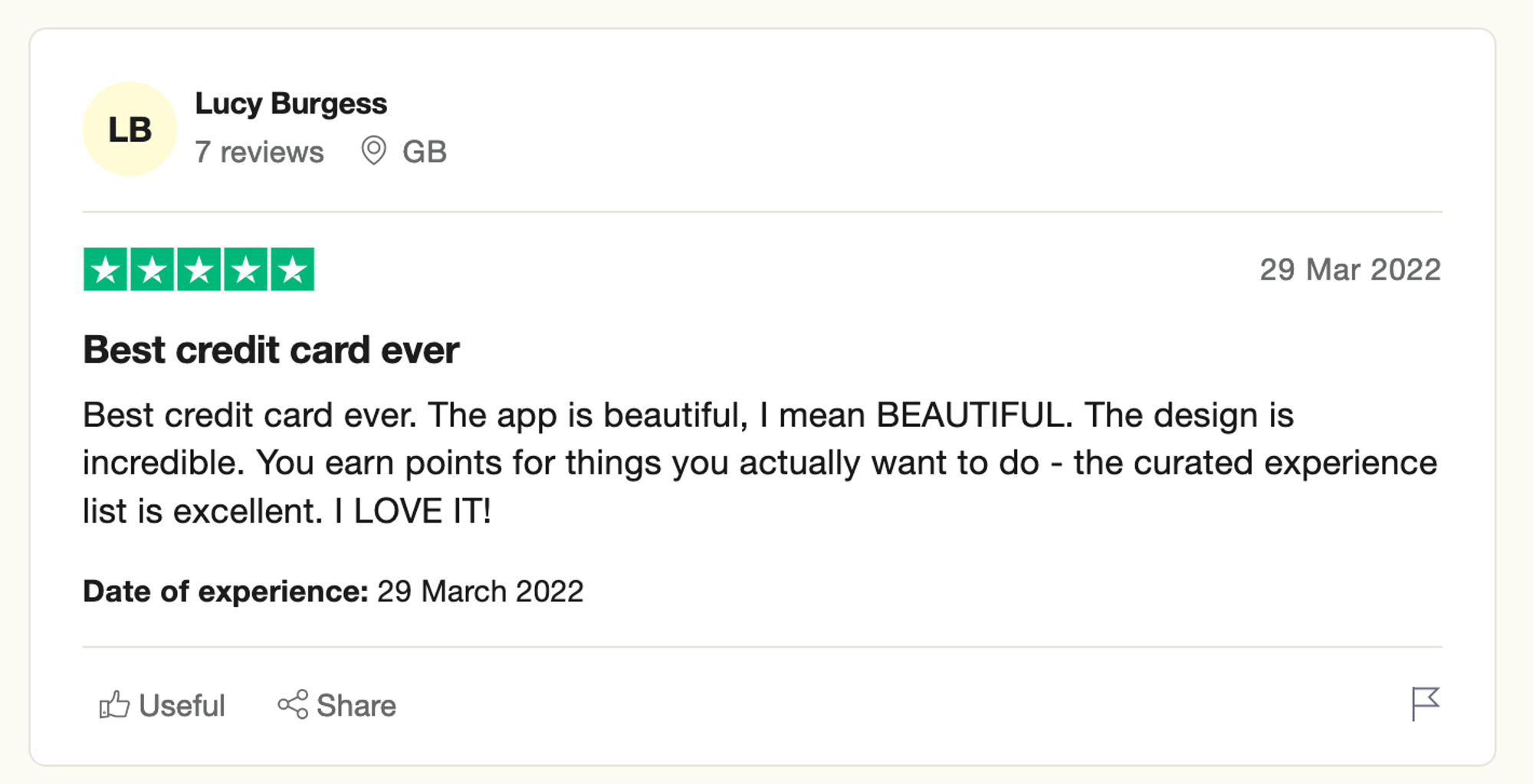

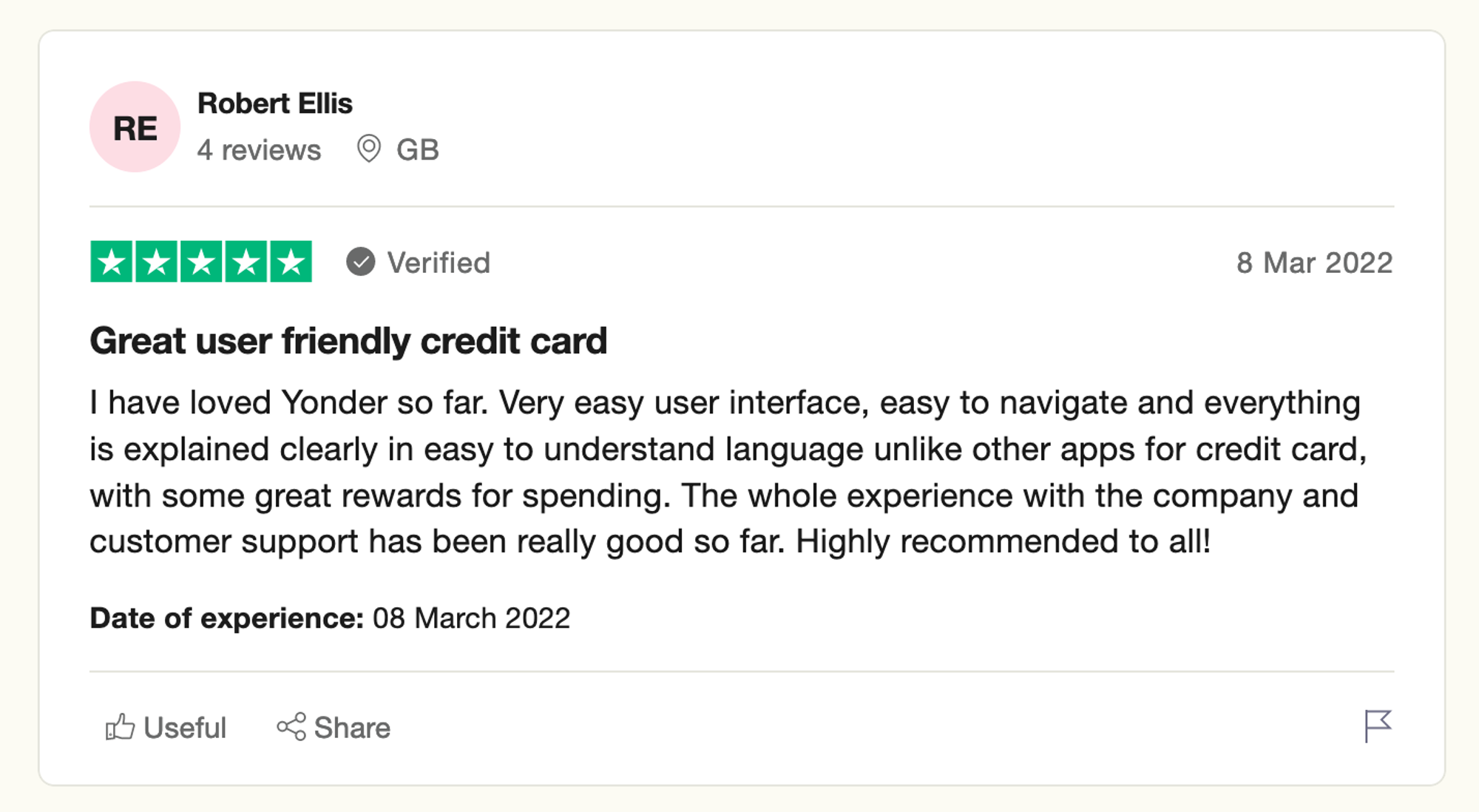

We launched. The reviews started coming in. I didn’t believe them at first. I thought they were fake.

We launched a #customer-love channel on Slack. Someone wrote to us that they had found the app’s onboarding to be the best they’d seen in a fintech app. I genuinely thought our onboarding was terrible. I lived in a weird disconnect during launch unable to accept people liked, even loved, the product. Was it perfectionism? I don’t think so. I still don’t know why I felt like that. The words were so positive. It felt weird. This is the UK, when do you say extremely positive things about anything?

I think in my head I'd imagined getting to the point where the product was loved would take longer. You can't hit a home run building an app in 9 months, right?

And then I got that email in April.

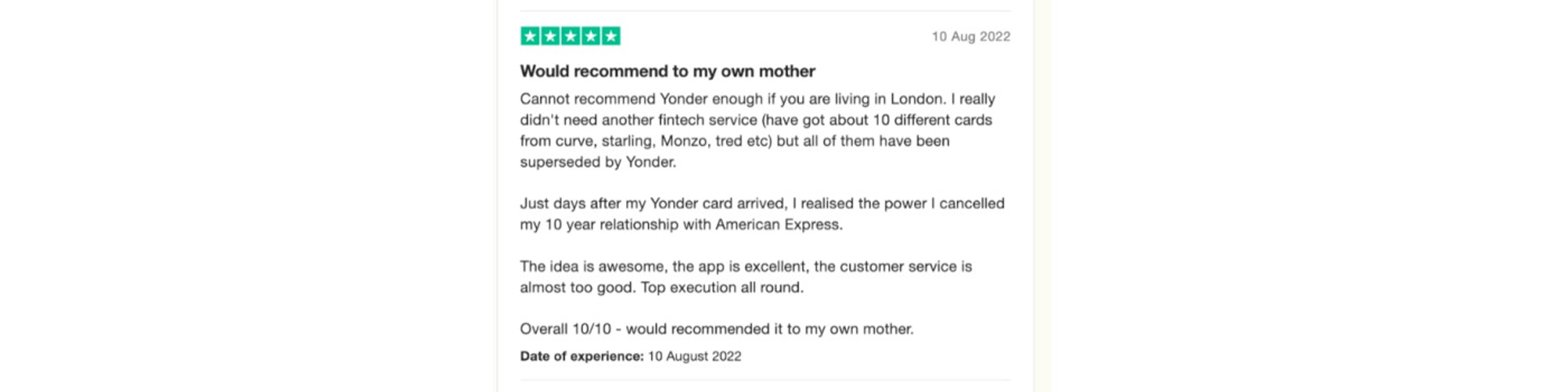

In August a review came through that’s still my favourite.

It wasn't until November that I got off a call with James who had been interning at Yonder weighing up joining full time or a PhD. I was walking around Camp’s Bay in Cape Town chatting to him on the phone. It was by going through all the future possibilities of Yonder, that I had a "glass shatter" moment of seeing what we had. I’d built the app, with the team. For about 5 months I experienced a new feeling I hadn’t felt before.

Excitingly, we’re still tiny. I still tell new joiners that Yonder is a rare opportunity, combining consumer fintech with consumer lifestyle. The customer love is rare. Every person who joins has an incredible ability to impact the company and where we go.

More writing about Yonder

- Tom has written lots more about Yonder on his Medium and LinkedIn Top learnings from 2024.

- James has written about Yonder in his personal report of 2023.

- Dominic, one of Yonder’s early investors wrote Yonder: a refreshing take on credit cards

- Tim wrote about how raising a Series A in a downturn on Sifted

What went wrong?

You can plan a pretty picnic but you can't predict the weather.

- Outkast

Note: During a draft of this I had feedback "would be good to know if anything went wrong along the way?". One of the (surprising) things about the first year is that nothing went catastrophically wrong. But there's always going to be something.

At the end of 2022 as the fintech/crypto bubble burst, and the downmarket and layoffs rippled through tech, Tim pulled off the impossible and raised a £63.5m Series A.

The fundraising event was so rare that that Sifted interviewed Tim.

During Spring of the following year we'd doubled the team size.

Late on a regular weeknight I checked my phone before going to bed and saw some noise about our bank Silicon Valley Bank, having "liquidity issues". I texted Tim, he replied “we're moving X million to HSBC tonight”. Good, Tim has it sorted.

Except that transfer never went through and our bank had collapsed. For 72 hours Yonder was most likely headed for bankruptcy.

I couldn't believe it. Startups fail because they run out of money, not because their bank runs out of money.

That weekend I walked around stunned just refreshing the news. It was pure shock, no sadness or anger, just "this can't be happening, this can't be Game Over".

Tim who was meant to be having a holiday, was rudely interrupted by millions of pounds disappearing. I wondered what the online banking looked like. Did it show the balance, but you couldn't move it? Did it show "Alert: Sorry, it's not that you've run out of money, it's us who's run out of money, and now you don't have any money."

But rather than panic Tim had written an emergency scenario plan of all possible outcomes. I carefully read it. There was a bunch of outcomes and they were all terrible. But the document had complete clarity. Almost as if there was no catastrophe or reason to panic. In my mind Tim ascended into legendary status. You build a new credit card, you build something people are loving, you get the near impossible Series A done, and life hits you in the face with a bank run. But you keep your cool.

And then with the UK government's help, HSBC bought our bank for £1, and guaranteed everyone's deposits.

That meant on Monday things continued on as normal.

We had an all-hands where Tim, who hadn't slept during the weekend delivered the news that everything was fine. The new employees that had kids and mortgages audibly sighed with relief. And then we all left the meeting, headed back to our desks, and got back to it.